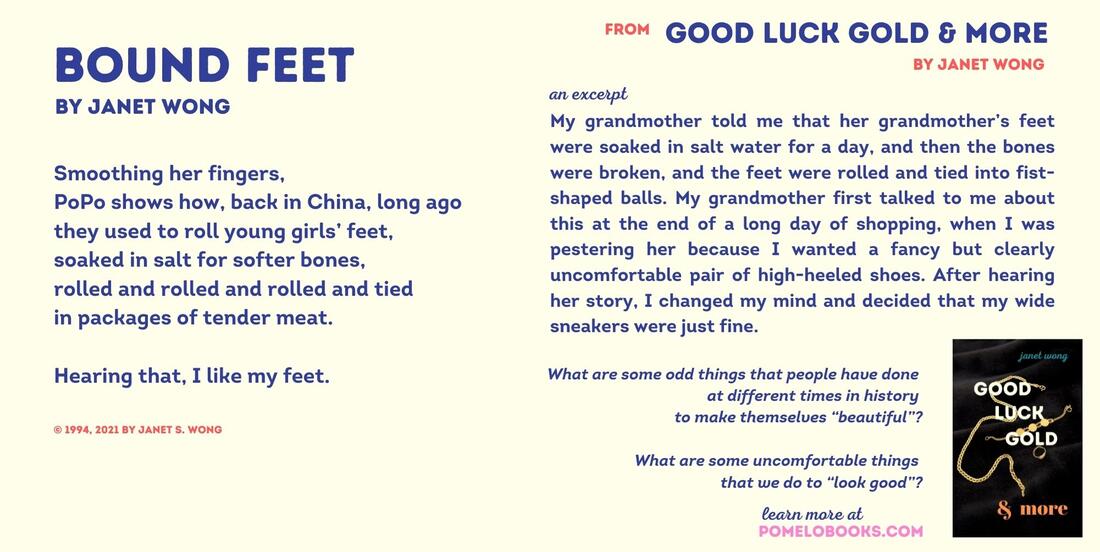

Be sure to head to Matt at Radio, Rhythm & Rhyme. He is hosting the Poetry Friday Round Up and celebrating the arrival of Friends & Anemones: Ocean Poems for Children, created by members of The Writer’s Loft in Sherborn, Massachusetts. Do you like challenges? The Poetry Sisters have an invitation: You’re invited to join our challenge for the month of November! We’re writing an Ode to Autumn. An ode is a lyrical poem, a way of marking an occasion with a song. Whether you choose an irregular ode with no set pattern or rhyme, or the ten-line, three-to-five stanza famed by Homer himself, we hope you’ll join us in singing in the season of leaf-fall and pie, and sharing on November 26th in a blog post and/or on social media with the tag #PoetryPals. The #inklings offer this challenge: “Write a poem that includes the idea of percentage or percent. Percentages are all around us in recipes, prices, assessments, statistics. Include the idea of percentage in your poem in some way.” Friends & Anemones: Ocean Poems for Children, created by members of The Writer’s Loft in Sherborn, Massachusetts, was officially published November 8, 2020!  I've been reading GOOD LUCK GOLD and MORE by Janet Wong. This is her re-issue and expanded collection of poems from her DEBUT book in 1994. I have the original book signed by her. I highly recommend this book be in every elementary and middle school for sure. These poems are timeless. I remember reading them twenty-seven years ago and being astonished by the treatment given to the author and now reading them they still give me pause at how some humans treat others. The “story behind the story” or “story after the story” additions are powerful and provide such a good bridge to talk to students about racism. JRM: GOOD LUCK GOLD was your debut book for kids in 1994. What was it like to take a class from Myra Cohn Livingston? JW: Myra Cohn Livingston mentored a whole generation of children’s poets in her Master Class in Poetry. This was a UCLA Extension class that was offered only to those Beginning Class alums who were invited by Myra; there was seldom an opening. As a result, Myra’s Beginning Class was full of students who had taken it five or more times and were not beginners at all: Monica Gunning, Kristine O’Connell George, Joan Bransfield Graham, and more. Some people who took Myra’s classes were published picture book writers who wanted to know more about poetic techniques: Alice Schertle, April Halprin Wayland, Ruth Bornstein, and Tony Johnston, for example. Earlier this year I was invited by Julie Hedlund to speak with the 12x12 group, and I felt like I was channeling Myra with my emphasis on assonance, consonance, and internal rhyme. Myra died in 1996, but you can still learn from her book Poem-Making: Ways to Begin Writing Poetry (now out of print, but you can find it at a library). JRM: And you can also find it at Thrift Books. GOOD LUCK GOLD was written twenty-seven years ago. How has life experiences informed you when writing the new content? JW: Five years ago, I thought that the discussions about anti-Asian racism weren’t really needed any longer. I was content to let the original GOOD LUCK GOLD rest in peace. But the recent surge in anti-Asian racism has scared me. I’m afraid for my 86-year-old father, worried that some crazy racist will attack him on the street. I’m even afraid for myself sometimes; I’ll think twice before walking somewhere alone. Because of all this, I felt an even greater urgency when writing the prose pieces about racism, an immediate need to connect with readers on a basic human level. JRM: I could see this book being a mentor text for students to write their own poems about their parents and grandparents, food, and culture. Have you worked with students to create their own collections? JW: In 2013 I worked with some students from Chadwick School in California to create anthologies—a 6th grade anthology and a 3rd grade anthology where every student was involved somehow: writing, illustrating, editing, copyediting, typing, doing technical work, and even marketing the books that they created, selling them on Amazon to raise funds for charity. I think those students really enjoyed having a “real world” publishing project. If schools want to embark on this kind of project for students in a certain grade or in a publishing club, I know that there are several poets who could provide guidance (for a fee). Jone, YOU would be an ideal poet to help schools make their own books. (Parent volunteers: raise some funds and hire Jone!) JRM: Was there one poem that was more challenging to write? JW: The poem “Bound Feet” went through many, many drafts. The prose piece, too. There is so much that can be said about the complicated history of foot-binding. After trying to write a narrative poem, I finally decided to keep the poem close to my own personal experience, writing about how I felt as a child when my grandmother first told me about her grandmother’s bound feet. When a poet—or any writer, even a writer of nonfiction for adults—is having difficulty with a topic, I think one good approach is to pretend that you are a child again and write from the child’s point of view. JRM: What would you like readers of this interview to know about #StopAsianHate and bystander training?

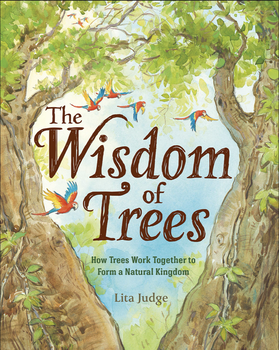

JW: The Hollaback! bystander training session is free and takes just one hour of your time; you can sign up in a minute at ihollaback.org. There are sessions focused on anti-Asian racism and also on different communities and issues. My main takeaway: as a bystander, we sometimes worry about getting involved because we know that we can’t fix the situation alone. And maybe we’re scared. But you don’t have to resolve the problem all by yourself. Just do something to get things started. You can distract. You can document. You can delay until more help arrives. Be the first bystander to step up, and others will follow. JRM: What is your next project? JW: Sylvia Vardell and I plan to continue with our Anthologies 101 and 201 courses next year, working on books similar to the THINGS WE DO book of ekphrastic poems with your fun poem "ZOOM,” Jone. People can learn more about these workshops at our website here. Next up for the January/February 2022 Anthologies 201 group is THINGS WE EAT, a topic near and dear to my heart (and stomach). One of the photos that Sylvia and I have selected features a Korean restaurant scene and the word "kimchi." I am super excited for that book—you could even say I’m hungry for it! For fun: Sylvia's and Janet's next project is THINGS WE EAT. What would be a food for the letter X? Comment below. Janet is generously sending 6 books to people who comment (3 from last week and 3 this week) I will announce the winners next FRIDAY, NOVEMBER 19. Thank you, Janet for providing readers with great back story about GOOD LUCK GOLD and More. Looking forward to the next books that you write. Well, today is the final day of April. End of National Poetry Month. I have loved every interview this month. Our Poetry Friday host is Matt at Radio, Rhythm & Rhyme and he has winners for books. I will have winners next week so be sure to comment on this or any of my posts for the month by Tuesday, May 4 (May the 4th be with you). I LOVE trees! And I was so excited to get this new book by Lita Judge. But first, not only is it Lita's interview and National Arbor Day, a little bird told me it was our guest's birthday!  Before you sat under that magnificent thousand year old oak, were there other experiences with trees that helped you form such a bond with them? LJ: I was born on an island off the coast of Alaska under the giant Douglas fir of the Tongass National Forest. So I grew up surrounded with trees. My dad was a soil scientist with the Forest Service and we spent much of my childhood living in some pretty remote areas. So from an early age I’ve had a great appreciation of nature, and especially trees! What led you to decide to write THE WISDOM OF TREES? LJ: I’ve always loved trees, and could identify different species, but I really didn’t know a lot of the recent science about them until I read a research paper talking about how trees communicated, how they fed one another, and even helped each other to fight against attacking insects. I began to realize that the stories trees had to tell were as startling and important as the stories I was creating. I knew I had to learn more about trees and write this book. Besides the research for the tree facts, what other research did you do? LJ: I read a lot of the latest research papers and talked to scientists but the most important thing was I traveled extensively to visit different forests both in America and Europe. In order to create the illustrations, I really needed to see different kinds of tree species than what I can find where I live, in New England. I needed to find ancient trees as well. I traveled to visit a yew tree in Northern Wales (UK) estimated to be nearly 4000 years old, and woodland preserves where the forest haven’t been logged and allowed to become old growth. I’ve been fortunate enough to see the bristlecone pines in Nevada which are some of the oldest trees alive. This all helped me to gain the understanding I needed to write the book as well as to illustrate it. In the process of writing the book, did the poems or the fact paragraphs come first? LJ: That’s hard to answer. When writing a book I don’t really follow a pattern. I just keep exploring in and around and through an idea. A thought occurs to me and I will tackle a poem. Or I will gain some knowledge to allow me to write the fact paragraphs. It is a lot of back-and-forth. I didn’t know from the beginning I wanted to use both poetry and expository nonfiction. I wanted to give the trees a voice through the poetry because the whole book is about the idea that trees have a language and can communicate. But I definitely wanted this book to be nonfiction and to cover a lot of interesting facts. Were there facts you wanted in the book but couldn’t put them in? LJ: Oh, there are always a mountain of facts that fall onto the cutting room floor when you write for children! I think you have to be really curious to write this kind of book, which means you are always diving into material you’ll never possibly be able to fit into the format. Sometimes I feel like I cut more than I keep, but it all goes into creating a book that presents material in a way that is approachable for children. I find people often think writing for children is easier than writing for adults. The particular challenge with writing for children is to understand the topic well enough that you can organize it in a clear and succinct manner. That always takes a huge amount of research and then the ability to find the focus which makes the topic clear. I think it is so fascinating that trees save one third of their food for fungi. What was your favorite or most surprising fact? LJ: I’m fascinated by how much goes on below the surface of the earth. We all love trees for their majestic beauty, and what we can see above the ground, but below ground, they are super organisms, connected to each other, communicating with one another, feeding one another, and helping each other. They have a cooperative wisdom. Their survival depends on the whole community working together. I am quite fond of all trees but the Oregon White Oak is one of my favorites. Do you have a favorite tree? LJ: I spent most of my school years in Oregon so I have a particular fondness for the Douglas fir. In the coastal rainforest of the Northwest they grow to be giants, with their gnarled branches covered in moss and lichen. I was married under these giant trees too. And during my ceremony we called in a pair of wild Spotted owls that lived and nested within their limbs. But I also love aspen. As I mention in the back matter of my book, these trees send up shoots from their roots that grow into genetically identical clones of the original tree. A colony of quaking aspen in Utah contains forty-seven thousand identical trees and is estimated to be around twelve thousand years old! As not only the author but also the illustrator, could you tell readers a bit about your process? LJ: My process always begins with a journal. I always carry my journal when I go out to observe and sketch. Working from life is a key part of my creativity and inspiration. All my books begin that way, even my fiction. When I begin each project, I draw long before I ever put a word to paper. I wish drawing was taught in school with subjects like science, and writing, not just for the purpose of creating art. Drawing is learning to see the world well enough to write about it as well as illustrated it. Drawing is a way for me to think about a topic, to understand it, to organize it. I begin with sketches drawn from nature. Then I go back into the studio and begin rough sketches on a storyboard that maps out the book. Only then do I really start putting words to paper. Eventually I do small color studies to get a vision of how the color will tie into the book. A book takes me three or four years to create but it’s only in the last few months that I start creating the watercolors that will eventually become the illustrations for the book. Was the written material completed before the illustrations? LJ: I’m always asked that, and to be honest it kind of startles me. I think there is an assumption that words come first. Perhaps because so many books are illustrated by somebody other than the author, in which case the drawings do come second. But as an author/illustrator I don’t see such a clear divide between the two parts. As I mentioned in the previous question I always begin by drawing. But once I start putting words to the paper I often will go back and change drawings. And then go back to the words. It’s a fluid process for me where I’m constantly shifting between the two forms to tell the story. It’s what I love about being able to do both. I can build up a book organically around the words and illustrations. It feels like such a natural fit for a picture book. What was the research like for the illustrations? LJ: Research for illustrations isn’t that much different than for writing. To draw something well for a non-fiction book you really have to understand it. So you learn everything you can about the topic. Whenever possible I work from life. Even for a book that covers historical topics, I will travel on location to find the right architecture, or to go to a museum where I can find examples of clothes that people wore, or the carriages they rode in. If there are people in the book, I will find models to draw from. That can be a lot of fun. I’ve had kids from our town frequently pose for the stories I create. In the case of the trees I go outside and draw them. I spend a lot of time at zoos and in nature to observe animals. Often when I’m drawing I’ll notice something that will make the written part of the book richer, because of the time I took observing and drawing. I love doing both for that reason. They just feed each other, the words and illustrations. I loved the two poems, “We are the Lofty” and “We are the Ancient”. If you were doing a reading, what poems might you read from this book? LJ: I would read "Song of Hunger". The concept that an injured tree can send out a message to her fellow trees, and they will answer by sending food along their roots — it’s just so beautiful. It’s what made me fall in love with this topic. And it was my favorite poem to write. What is your current writing project? LJ: I have several projects in the works. I am working on a nonfiction book about the evolution of dogs which involves even more research than the trees, perhaps. I also have a fiction book about friendship that is young and whimsical and has been a very joyful piece to work on. And I have another book that is, so far, wordless and hard to describe because it explores creativity and imagination, but in a visual way. So I guess that’s not a writing project. But that’s the nature of the work I do, sometimes my books are almost purely visual. Sometimes words come late in the stage. Who knows what will happen with this one. That is part of the wonderful mystery of creating. What is one of the best things that readers can do to help the future of forests? LJ: Think about the products we use every day, the piles of paper we write on, toilet paper, food packaging, etc, and just try to use less. We consume so much in our daily lives. And sadly so much of it isn’t something we really need. We do things out of convenience and that can be thoughtless for the planet. Reuse containers and recycle paper. And with the trees themselves we need to protect the older trees and snags (dead trees). These make the best homes for wildlife. So often people will cut down a dead tree because they think it is unsightly or dangerous. When in fact it is home and food to countless animals and insects. Make informed food choices — every year forested land is cleared for grazing livestock. Also educate your friends and family about how trees help our planet, and how our actions affect forests around the world. Plant native trees in your yard. Trees native to your region will promote healthy insect and wildlife diversity. Thank you, Lita for a wonderful interview. I hope it's filled with trees, poetry and cake. Before You Go...You might want to read these pervious interviews if you haven't yet. Next week I will announce winners for some of these books.

I have five great interviews lined up: April 2 POETRY FRIDAY: ALLAN WOLF April 9 POETRY FRIDAY: LISA FIPPS April 16 POETRY FRIDAY: CHRIS BARON April 23 POETRY FRIDAY: JOANNE ROSSMASSLER FRITZ April 30 POETRY FRIDAY: LITA JUDGE I love getting books into the hands of readers so there will be prizes for stopping by and saying hi.  Welcome, welcome! Today all the poetry goodness of the world will be found at Catherine at Reading to the Core. It's my fifteenth year of participating (some years better than others). I have five great interviews lined up: April 2 POETRY FRIDAY: ALLAN WOLF April 9 POETRY FRIDAY: LISA FIPPS April 16 POETRY FRIDAY: CHRIS BARON April 23 POETRY FRIDAY: JOANNE ROSSMASSLER FRITZ April 30 POETRY FRIDAY: LITA JUDGE I love getting books into the hands of readers so there will be prizes for stopping by and saying hi. What inspired you to write EVERYWHERE BLUE?

JRF: EVERYWHERE BLUE was woven together from many different threads. In 2013 and 2014, I had been writing poetry and submitting to literary journals. After one journal accepted two of my prose poems, I started writing a poem about oboe lessons. I played the oboe in junior high and although it had been a long time, I could still remember the crushed-leaf taste of the reed! That was the beginning of what would become EVERYWHERE BLUE. I always knew it would start in November. I get the sense that the environment, family, and music have always been important to you. Can you tell me more about that? JRF: We were a close family and I grew up the youngest of three siblings, surrounded by books and music. My mother took us to the library every week, and my early memories include following her around the house with a library book tucked under my arm, saying, "Mommy, would you read to me?" My parents were always playing records on the hi-fi, mostly classical but also Broadway show tunes. So music filled our small house. As for the environment, I can remember the first Earth Day in 1970. I was in tenth grade and we had a special assembly. Inspired, I walked home from school that day, instead of taking the bus, and I picked up trash along the highway! Soon after, I wrote a letter to our township commissioners, asking them to start a recycling center. I'm sure I've worried about the environment ever since then. Maddie has an undiagnosed anxiety condition, was that a challenge to write? JRF:I've suffered from mild anxiety most of my life, so it wasn't that much of a challenge to give Maddie some of my own symptoms (the stomach issues, the nervousness, the heart palpitations). But the story needed more, so I did lots of research. I read a lot of books about OCD in kids, and kids who worry. Did you have characters that were easier or more difficult to write? JRF:The kids were easier for me to write than the parents! Both parents were flat characters in the beginning. Even though I'm a parent myself (of two grown sons), I had to work on bringing Maman and Daddy to life. This is why I much prefer revision, because I could see them becoming more real with each draft. Strum was also difficult to write about because we only get to know him through the memories of other characters. My wonderful editor, Sally Morgridge, had me add even more flashbacks. What kind of research did you do for the book? JRF: I've already mentioned the anxiety and OCD research, but i also did lots of research on the climate crisis, much of which didn't even make it into the book. For instance, I spent a long time researching frozen methane hydrates, and then as I revised the novel, that information didn't seem necessary. But all research is fascinating and educational, so I didn't mind. How did you come up with the color blue as an image? JRF:The color blue appeared early on in my rough draft, because I knew from the beginning I wanted a scene with the Butterfly Farm and Maddie and Strum chasing blue morphos inside the screened-in area. From there, it seemed natural to expand the mentions of blue. And blue can symbolize so much. It can be a bright happy color, or a symbol of depression. The poem "Anything With Blue In It", about learning some new music, Gershwin's Rhapsody in Blue, was one of the later additions to the book. I loved that each section of the book is a musical term. How did you come up with this idea, was it a revision thought? JRF:Thank you for saying that! I always knew that I wanted to start with a diminuendo. That first poem (revised many times) has been the first poem all along. Then, because I'm a pantser, the idea just naturally grew from there. I knew all along I wanted Maddie to be musical, and that there would be plenty of musical terms. It occurred to me one day that I needed four parts, because a symphony has four parts. I really liked that you addressed a common theme of parent’s expectations of their children. I think that will resonate with readers. Was that something you experienced? JRF:My parents never had unreasonable expectations for us. I think that's a consequence of being born a girl in the 1950s! Back then, it was understood that I would grow up and get married. Although I have the impression my parents told us we could be anything we wanted to be. There was no pressure. My mother was a stay-at-home Mom until I was in high school. Then she went back and finished her college degree and continued on to earn a Masters in Library Science.We were in college at the same time! Not the same college, though. She then became the Archivist at the Philadelphia Museum of Art. So in a way, she defied her own generation's expectations. Do you have a favorite scene or quote from the book? If you were to give a reading, what might you read to the audience? JRF:Not one favorite scene or quote, no. But I do have several favorite poems or even favorite stanzas within poems. One of my favorite scenes has always been the ending scene. I think if I gave a reading, though, I'd probably recite "I Am a Walking Fraction" or "Butterfly Dreams". I’ve been taking some classes at the Highlights Foundation with Cordelia Jensen. We've been discussing what is the definition of a verse novel? What are your thoughts on the definition? JRF:Oh, how nice for you! Isn't the Highlights Foundation wonderful? I wrote some of my best poems in Cabin 9 in 2016 and again in 2017! I know it's virtual this year because of the pandemic, but I'm sure it's still inspiring. And Cordelia Jensen would be a wonderful teacher. I suspect every verse novelist would come up with their own definition of a verse novel! It's not just poetry. I'd say it's a novel told in an interconnected series of poems. The story is almost more important than the poetry. But the poetry needs to be beautiful and inspiring too. Novels in verse tend to be more personal and emotional, and are always first person, nearly always present tense. Mine started out as nothing but free verse, as most verse novels do. It was my agent, Barbara Krasner (herself a writer) who insisted I add a villanelle at a moment of despair (the poem "Leaving", the most challenging poem I had to write!) and several rhyming couplets and tercets. I also have two haiku in my novel. What is your current writing project? JRF:My current WIP is nowhere near finished, so I don't want to say too much about it! But I am writing about brain aneurysms. I know, it's a strange topic for a novel in verse, but I've survived two ruptures and it's time I wrote about it! Thanks for allowing me to interview you, JRF:Thank you, Jone! I really appreciate you taking the time to interview me, and appreciate your thoughtful questions. And hold on, dear readers...Joanne has donated a copy as prize when the book is released in June. It will be for a US reader and will be signed, SQUEE!!! Thank you, Joanne!  Welcome to 2021 National Poetry Month. It's my fifteenth year of participating (some years better than others). Today Poetry Friday is held at Jama at Jama's Alphabet Soup and she has quite the alphabet soup feast for us. I have five great interviews lined up: April 2 POETRY FRIDAY: ALLAN WOLF April 9 POETRY FRIDAY: LISA FIPPS April 16 POETRY FRIDAY: CHRIS BARON April 23 POETRY FRIDAY: JOANNE ROSSMASSLER FRITZ April 30 POETRY FRIDAY: LITA JUDGE I love getting books into the hands of readers so there will be prizes for stopping by and saying hi. Today, I am thrilled to be hosting Chris Baron as he answers questions about his second book, THE MAGICAL IMPERFECT. This book will be available June 2021. THE MAGICAL IMPERFECT was just what I needed to read now. I remembered that 1989 quake and where I was (In Vancouver, WA, watching the World Series). The story of Etan and Malia shows readers the power of friendship as well as the strength of compassion. And I love the bond between Eta and his father and Grandfather as well as Malia and her family. I wish that when I was a K5 Teacher Librarian, that I had had a copy of the book. I had one student who had extreme eczema and there were days I could see her discomfort and pain. It would have been so cool to have a book that she could see herself in. WELCOME CHRIS BARONMy questions:

When did you know that this is the story you would write for your next book? (were you still working on ALL OF ME?) What was the spark that started you writing it? Baron: Love this question: I think the quiet voices were stirring for a long time. Having lived in the Bay Area, the magic of that place is present in almost all of my stories. It was really when I started thinking about my grandfather who was a jeweler in Brooklyn that the story started taking shape. I had some great conversations with my agent about my ideas for this story--about two unlikely friends--kids-helping one another, and it grew from there. Did anyone in your family arrive in the states via Angel Island? This place as an entry spot is new to me. I had no idea. Baron: It’s fascinating to see the history. I am familiar with the history, and my family actually arrived through Ellis Island while my wife’s family emigrated from the Philippines in the 1960s, so there is a lot of family history connected with ports of entry and the movement from an entirely different culture into a “new world.” Angel Island history is lesser known than Ellis Island. There were many immigrants who came through, Japanese, Filipino, remnants of Jews fleeing Europe. It’s a place of deep pain for so many, and there is much to be written about here--primarily the roughly 175,000 Chinese Immigrants that came through and the countless numbers who were interrogated or detained. A fantastic resource to learn more about Angel Island and all that happened there is from this book which was a core source of my research: Angel Island: Immigrant Gateway to America, by Erika Lee and Judy Yung. Also--two other books I highly recommend are: Paper Son: The Inspiring Story of Tyrus Wong, Immigrant and Artist, and Paper Son: Lee's Journey to America by Helen Foster James and Virginia Shin-Mui Loh. As a child did you experience selective mutism or bullying? What kind of research did you do for the book? Baron: So MUCH RESEARCH! I spent time in our College Library, working with our Mental Health Department to learn all I could. I also highly recommend After Zero, by Christina Collins, for a really powerful story about selective Mutism. Most of all, I relied on my own experience in dealing with this. As a kid, we moved a lot. One of the ways I dealt with the anxiety of moving was the manifestation of mild selective mutism. It was easier to stay inside my imagination than give my words away. It never lasted long, and certainly others deal with much more severe cases than this, but I think I have a strong taste of it. As for bullying: Not talking often invited some sort of cruelty--but the real bullying for me was almost always about my weight (see ALL OF ME). Were you living in the San Francisco area in 1989? Baron: I lived in the Bay Area before 1989, but I still had family and friends living there during that tumultuous time. What led you to the decision to create the fictional town of Ship’s Haven ( I do love the name)? Wouldn’t it have been just as easy to use a real town? Baron: I love this question. I always draw maps-maps are such a huge part of my writing process. There were a few towns I considered as candidates, but I always envisioned a small town on the coast bordered by redwoods. The deeper I went into the magic of this town, it’s diverse inhabitants, and the roots of the story--Ship’s haven came alive. Were there any characters that were more of a challenge to write? Baron: Yes and no. But isn’t this true for all writers? (smile). I think I always want to create the most authentic characters I can--so each character took a lot of time and “extra” writing to ensure they came alive in the best way possible. I think the greatest challenge was to make sure that the rich culture and history of the characters were fully and appropriately represented, so I spent a lot of time, for example, working with my wife on Malia’s character. I also had several sensitivity readers for different aspects of the story. This really helped me through different characterizations of everyone. I loved the bareket scenes. It hit home to have lost and regain a family treasure. What is the story behind the bareket. The return and the tiny rabbit footprints around it gives it a sense of magical realism. Baron: I am SO glad to hear this. The bareket scenes were close to my heart. I wanted a jewel that had a sacred and symbolic life, a symbol of deep hope. My grandfather worked in a jewelry shop in Brooklyn--nothing fancy--trophies, watch repair, stuff like that. But whenever I went to see him he always had a treasure for me--something solid I could hold in my hand. I wanted Etan to have this, too. There are so many magical moments in this story: the talking to the trees, the clay, the treasure box. Again, what are the backstories for them? (I’m a tree talker so I get it). Baron: Without too many spoilers--I would say that this story is rooted in the idea that magic is all around us--that if we might only stop and listen-pay attention-we will see and hear the trees, or discover the ancient things living right beside us. But also--I love trees. Malia’s cape does a lot of work in the story. I loved the ending image of the cape (I don’t want to give it away). Where did this image come from? Baron: It does! So much of the book deals with Malia’s severe skin condition. These images relate to the life I have lived with my wife and her severe eczema--learning to hide and to be brave at different times. It’s a deep well in our lives, and the cape comes from there. I wanted to know more about the mother, I almost wondered at the end of the book if there is another book there about her and Etan. I loved that they both are notebooks. Baron: Ohhhhhhh, yes. I like this idea. She and Etan have a very special connection, and this is part of why it hits him so hard when she has to leave. The notebook is an extension of herself that she gifts to him. I think as a parent-writing Etan’s mother and father felt like two sides of a coin. Parents often express themselves differently even when they both love their child with all of who they are. It felt close writing both--even as they were so different. Do you keep a notebook? What is your writing routine? Baron: I have a giant notebook that I draw in, write ideas, and of course, maps. I confess though that my kids often take it and draw surprise pictures inside (which I love). Do you have a favorite scene or quote from the book? If you were to give a reading, what might you read to the audience? Baron: I think there is a scene where Etan first meets Malia that I have read to a few classes at school visits. In these scenes, Malia stays hidden behind her door, but at the very end of their time together, Malia’s irrepressible vitality comes through like a light shining under the door and into Etan’s heart. Goodbye, Etan the artist. Please bring me a pumpkin if you can. And for a moment I see half of her face smiling, as she closes the door. Finally, I’ve been taking some classes at the Highlights Foundation with Cordelia Jensen. We’ve been discussing what is the definition of a verse novel. What are your thoughts on the definition? Baron: Cordelia is amazing. I am not sure what more I can add to the definition, but I can say that for me Novels in verse relate to all kinds of readers. There are all the elements of fiction at work, plot, character, setting, theme, conflict, all at work. but it’s delivered in the most careful way possible. There is space on the page, measured breaks, pacing, music,figurative language, and movement of lines that a reader of almost any level can find their way into. The structure of verse creates an intimacy with a reader that allows them to hear the tone and cadence of a character’s voice. This can create even stronger connections for readers. Thank you for taking the time to answer my questions, Chris. I hope that many will be sure to put this on their lists of "Books-to-Buy-in-June" list. That's when it will be available.  Welcome to 2021 National Poetry Month. It's my fifteenth year of participating (some years better than others). This year I'm taking a look at some previous poems that I enjoyed and will be revising. Some have been on the blog before and others not. I have five great interviews lined up: April 2 POETRY FRIDAY: ALLAN WOLF April 9 POETRY FRIDAY: LISA FIPPS April 16 POETRY FRIDAY: CHRIS BARON April 23 POETRY FRIDAY: JOANNE ROSSMASSLER FRITZ April 30 POETRY FRIDAY: LITA JUDGE I love getting books into the hands of readers so there will be prizes for stopping by and saying hi. WELCOME AUTHOR LISA FIPPSWhen I decided to interview novel in verse authors, I wanted to feature a couple of debut authors. Thanks to Sylvia Vardell's fabulous 2021 Sneak Peek post for all poetry books, I discovered Author Lisa Fipps. I read this book in one sitting. I fell in love with the main character, Ellie, and how she grows throughout the book. I felt the sting of some the Mom comments. What led you to write STARFISH? Was there a reason for choosing to write in free verse instead of prose? FIPPS: I wrote Starfish because it was the book I needed when I was a kid. I was bullied relentlessly for being fat and struggled with so many emotions from all the bullying. Since I was an avid reader, I turned to books, hoping to read a story like mine, hoping to feel less alone, hoping to find help with how to handle it all. But a book like that was nowhere to be found. I ended up feeling even more alone. More different. I’ve always dreamed of writing for children, so it only made sense for my debut novel to be the book I always needed as a kid. I’m really surprised and saddened that from the time I was a kid until now – all those years – a book like Starfish didn’t exist. We need fat- and body-positive books for kids featuring fat protagonists, especially since nearly 75 percent of adult Americans and a great percentage of kids are fat. I’m starting to see more and more children’s books with fat protagonists, so that makes me happy. There’s still a long way to go, though. I wrote Starfish in verse because that’s just how stories come to me. I like it because it allows me to cut to the emotional core of a story quicker than prose. Using fewer words also gives me that staccato effect I love. Were there characters that were easier or more difficult to write? Were they based on anyone? FIPPS: Ellie is based a lot on me, so that made it easier to write her story, at least when it came to what happened to her and how she felt. What made it hard was digging up, facing, and reliving past hurts. The dad was hard to write. On a personal level, I have no idea what a dad is like or what it’s like to have a dad. My dad died when I was thirteen months old. A lot of readers love the dad. One reader who found out I grew up without a dad said, “Do you think you wrote the dad you wished you’d had?” And it dawned on me that that’s exactly what I did, without making a conscious effort to do so. Ellie’s dad is the dad I literally daydreamed about having when I was a kid. I loved the images of the starfish and the whales throughout the book. What led you to choosing those images? I loved the poem “Whaling Wall” when Ellie sees the beauty of humpback whales. FIPPS: When you’re fat, there always seems to be this one defining moment when everything changes, the moment you go from being a regular kid/person to being the fat kid/person. For Ellie, that came during her under-the-sea-themed birthday party, where she wore a whale swimsuit. She cannonballed into the pool, creating a big splash. From them on she was called Splash or some synonym for whale. That’s why I used the whale image in the book. The starfish image came from the scene where Ellie starts thinking that maybe it’s okay to be herself, to be seen, to be heard, to take up space. When she’s trying to imagine what that would be like, she stretches out in the pool and takes up all the room she wants. She literally looks like a starfish, with her arms and legs stretched out. When she starts to face the bullies and defend herself, she notices she takes the starfish stance: Arms stretched out and feet more than shoulder width apart. I think that the word starfish and the image that pops into your head when you hear or read it, gives you a perfect visual of being free to take up all the space you want in the world. Were the images in the first draft or did they appear in later drafts? FIPPS: The whale and starfish images were in the story from the beginning, although I added more emphasis to the starfish as I revised. Do you have a favorite scene or quote from the book? FIPPS: I think the scene where Ellie starfishes and says “behold the thing” as she confronts her mom is my favorite. It is the defining moment for Ellie. For their relationship. But it was so emotional for me to think about, let alone write, that I will never read that poem aloud. I noticed that use you used the library for some scenes in the book. How did being a librarian inform you that there needed to be a library in the book? (Being a retired K5 librarian, I notice when books feature a library) FIPPS: I am the director of marketing for a public library, but I’m not a librarian. I included libraries in Starfish because they were my refuge when I was in school. And, as an avid reader whose family was too poor to buy a lot of books, I visited the school and public libraries all the time when I was growing up. Coming home with a stack of books felt like Christmas. If you were to give a reading, what might you read to the audience? FIPPS: I always enjoy reading a few poems from the beginning and the poems with Dr. Woodn’t-you-like-to-know. They’re just fun to read. I’ve been taking some classes at the Highlights Foundation with Cordelia Jense. We’ve been discussing what is the definition of a verse novel? What are your thoughts on the definition? (As the once chair of the CYBILS Award Poetry category, we wrestled with where the verse novels belonged in Poetry or in Fiction or their own category.) FIPPS: To me, anyway, verse is poetry but it’s also its own creature. It’s a living, breathing, changing artform. You can bend and shape it any way you want it. That’s the beauty of it. It really feels like clay in my hands. What is next up for you? Do you have any new books in the works? FIPPS: Like all writers, I’m always writing. Stay tuned to social media for some exciting news in the future. How did you decide on Author Lisa Fipps and not just Lisa Fipps? FIPPS: Great question! Lisa Fipps is a common name and so is Lisa Phipps. A lot of people spell my name wrong. Fun fact. When I was a journalist, other reporters in the newsroom got sick and tired of hearing me say, “Lisa Fipps. F as in Frank, i, p as in Paul, p as in Paul, S as in Sam” every time I had to leave a message for someone to call me back. I got sick and tired of hearing me say it. You’d think it’d be an easy name to get right. It’s five letters. One syllable. Alas, it is not. I kept track of the misspellings. There were thirty-four, including Slitz, Flips, and Phillips. I thought the most common misspelling would be Phipps. It wasn’t. It was Simpson. I can only guess that people thought of Lisa Simpson from the TV show when I was trying to spell my name. Dunno. Weird. Anyway, I thought if I branded myself as Author Lisa Fipps for my website and social media that it’d help people find me since it is a common name – although, apparently, wretchedly hard to spell. Lol. Did you read BLUBBER by Judy Blume as a kid? It's been so long since I've read it, but it came to mind as I read your book. FIPPS: I didn’t read Blubber when I was a kid. It was a popular book, and I had planned on reading it. But then when we were in line after library time, getting ready to head back to our classroom, a boy saw a girl holding that book and said, “Blubber’s reading Blubber.” The girl wasn’t fat by any stretch. So, I was afraid to be seen reading it, knowing it’d give the other kids another reason to bully me. That’s one reason I chose the title Starfish for my book. It’s not a title that a kid would be embarrassed to be seen carrying or reading. Thank you, Lisa, for sharing this book with the world and for allowing me to interview you.  Wondering about my National Poetry Month Project? Here's what I have been up to since April 1, 2021: April 1: Welcome and Morning Prayer April 2: Interview with Allan Wolf April 5 Redux: "Outside My Window" April 6: Sun/Grian April 7: Adelanto/A Day's Journey April 8: Wings Redux Stop by, leave a comment and get entered for book giveaways at the end of the month. Many thanks to Tabatha at The Opposite of Indifference who is hosting Poetry Friday. She has a great project with translating poems into a second language.  The Poetry Friday Round Up is over at Mary Lee at A Year of Reading  If you are looking for a book that examines the lives of the Donner Party in a poetic manner and historical detail, read THE SNOW FELL THREE GRAVES DEEP by Allan Wolf. He graciously agreed to some questions recently. What led you to write THE SNOW FELL THREE GRAVES DEEP? I’m always on the lookout for historical subject matter. Some event that folks think they know about. And as I’m a disciple of narrative pointillism, I seek out events with multiple witnesses from all walks of life. The main element of narrative pointillism is the exploration of a single event from multiple points of view. I’m also motivated by visual images (stage coaches, horse-drawn wagons, mortuaries, period clothing, hats, cannibalism, graveyards, rivers, zombie mules, sentient icebergs, rats that sing opera, etc). The images (and the objects within the images) can actually resonate with the heart of a story, and thus a harmonic relationship forms. That’s how I get ideas: by looking at a whole mess o’ stuff and then standing back to see some sort of order in the seeming chaos. To connect and combine and to reassemble. When you were researching NEW FOUND LAND, did something pop up that piqued your curiosity about the Donner Party? Yes, the research for New Found Land certainly led me to other ideas for many other books. In fact, my novel Zane’s Trace was a direct result. Researching one of the Lewis and Clark expedition members, I saw the name “Zane’s Trace” on an old map. I knew then and there, that would be the title of my next book. I wrote another novel about Sacagawea and her son, Jean Baptiste Charbonneau (never published) that led me to explore the Oregon trail and the Westward Expansion of the 1840s-1860s. I had to write a book that will never be published in order to write the book that was published. What was involved with researching for the book? What was the process? I read a bazillion books. Starting with the oldest and working my way up to the more modern. By doing this you get a feel for how the historical facts have evolved over time. Then you go back and reread the earlier books. The second reading is always so much richer, since by then you have a good context and you’ve built your “prior knowledge” base. Researching for historical fiction is an exercise in vetting resources. You begin to see which books are responsible for spreading mistruths and which books suffer from racial, class, and moral biases. I also deprived myself a bit. I would go out in the winter without a coat. I made a bunch of campfires. I interviewed a fellow who had intentionally starved himself. My friend, Klaus, who lives across the street from me, was diagnosed with cancer of the esophagus and died, all while I was writing this book. Klaus was a German and I modeled the book’s German character, Ludwig Keseberg, after him. Klaus was healthy and strong as an ox, but he couldn’t eat because of the tumor. So, I watched him pretty much starve to death. I dedicated the book to him. He was a great guy and a good friend. Was there anything you discovered that you chose not to put it in the book? Yes. Quite a bit. The actual details of what happened are complex and, frankly, tedious. There were countless rescue attempts, countless attempts to hike out, countless miles of wilderness covered. And the nearly ninety emigrants would separate into multiple parties, constantly diverging and reconverging like some kind of amoeba! It’s enough to make your head swim. I had to leave details out. Believe it or not, I actually left out one murder (that of a Mr. Wolfinger by another party member). There were already plenty of murders without it. I know it seems like an outrageous detail to leave out, but it just made an already complex constellation of events even more complex. How did your research inform the voices of your characters? The voices of Hunger, Tamzene Donner, and Patty Reed really resonated with me. Voice (and everything else) is born from research. You just have to listen. There is a staple story, in Donner Party lore, of nine-year-old Patty Reed maturely comforting her mother and accepting that she may not survive. The story may (or may not) be completely bogus, but it led me to think of Patty as an angel with a direct line to God. Then you have snow angels. Angels have wings to fly over mountains. You see how the connections begin to, well, snowball. My Tamzene Donner research included the big bonus of having access to her personal letters, so her voice was immediate. Hunger was such a perfect narrator. How did you know it would be the narrator. Hunger was just intuition. It probably came to me in the shower. (I call these “meteor showers” ‘cause the ideas just start dropping from the heavens.) Hunger is a narrator and a narrative device, the glue to give shape to the overall story. The iceberg played this part in The Watch that Ends the Night. The Newfoundland dog played this part in New Found Land. I needed a character that could easily place the story in context to history (past, present, and future). I’m writing a novel now in which the narrator is a lake. It was quite a cast of characters, how did you determine who you included? Were there characters that were easier or more difficult to write? All potential characters must go through an “audition” phase. I’m like a casting director. Looking for variety. Looking for foils. Characters that will play well off one another. And I want all races, ages, genders, and personality types represented. Another thing I look for is how characters “fit” with the setting and the props and the costumes. A character might have a doll or a pair of oxen, for example, that they can interact with and against. And I often look for two characters that work together as a team—I call this a pair-acter. (Think the Weasley Twins, or Luis and Salvador in Three Graves Deep). I appreciate that you shed light on the unjust and slave treatment of the Washoe and Miwok people. What suggestions do you have for readers to find out more? To get an excellent overview I recommend The Other Slavery: The Uncovered Story of Indian Enslavement in America by Andrés Reséndez. For a more complete list, I’ve included a bibliography in my own book’s back matter. The North American history of slavery, the Reconstruction, Westward Expansion, Jim Crow Laws, Civil Rights and the Black Lives Matter movement, plus the relentless, systematic, and systemic degradation of Asians, Mexicans, and Native Americans—the more you understand our history, the more you see how these are all sister stars in the same evil constellation. One of my favorite scenes in the book is when Tamzene Donner quotes Tennyson and you can clearly feel how things are unraveling. And this line, Flames devour the poetry as I bring the kettle to boil.” Chilling. And you might add, Tamzene is boiling water so she can cook the family dog. Oh, I liked that scene too. That was a fun one to write—Tamzene realizing how powerless her intellect is in the face of such primal suffering. As a poet myself, I often feel this way to some degree. Poetry in itself will not pay the bills. You cannot eat a metaphor. BTW, I was incredibly sad when Tamzene died. I really liked her character. (And of course, I knew she would beforehand but still…) Yeah. I was sad to see her go too. Do you have a favorite scene or quote from the book? The romantic in me really likes the “budding love” scenes between thirteen-year-old Virginia Reed and her boo, Eddie Breen. I’m also fond of the opening and closing scenes for their pleasing cinematic quality. A favorite quote comes from Hunger who says the the first line of the novel: “None of this is my fault.” If you were to give a reading, what might you read to the audience? I would like to read the passage that opens Part Six, on page 271, in which Hunger explains the stages of starvation. It is morbid but beautiful. I’ve been taking some classes at the Highlights Foundation with Cordelia Jense. We’ve been discussing what is the definition of a verse novel? What are your thoughts on the definition? (As the once chair of the CYBILS Award Poetry category, we wrestled with where the verse novels belonged. In Poetry or in Fiction or their own category.) Is it a “novel in verse” or a “verse novel?” Or shall we call it a “Versnel” or a “Noversel.” I like to think of my own longform style narratives as a “hybrid novel.” My editor, Elizabeth Bicknell, has called them “postmodern.” But what is it? I like to picture a spectrum of literature as vast and inclusive as the stars. Genres and taxonomies allow us to keep track of things, but they never tell the real story. I could argue that Billy Collins is a fiction writer who writes poems. I could argue that Thomas Wolfe and Virginia Woolf are poets writing novels. In my “novel,” The Watch that Ends the Night, the iceberg speaks in iambic pentameter. As the iceberg melts, so does the metrical length of the lines, from pentameter, to tetrameter, to trimeter, to a single iamb. I would call that poetry, I’d guess. And are verse and poetry one and the same? (I personally don’t think so, but that’s a topic for another time.) Words give a poem sense, while the space between the words give it resonance. Poets can arrange words based on craft, style, and clarity, just as prose writers do. But poets don’t have to stop there. Poets can arrange words based on prescribed patterns . . . or not. Poets can even arrange words wherever the words instruct them too. Space is key. Space between words. Space between lines. You can even remove a word, like you would remove a superfluous wisdom tooth. Line-breaks can be purposefully clunky or smooth. When a line breaks, the words turn. The poem’s rhythm may also turn. The poem’s pace may turn as well. The reader’s eyes, heartbeat, and attention all turn. (Bonus Fact: The word “verse” comes from the Latin, verso, to turn.) The poet chooses where the lines break. The power of ‘the space between’ is on display, in a big way, in the “verse novel.” Scenes (or beats) in the plot don’t require the same continuity that we find in prose. As the writer it can be easier to maneuver the narrative when you have spaces and turns in your toolbox. As the reader it can be easier to read and remain engaged. The reader’s eyes are actively engaged as the line-breaks urge them on. The reader’s mind gets to take smaller bites and needs less time to chew. I noticed you just released NO BUDDY LIKE A BOOK. Do you work on verse novels and picture books simultaneously or switch back and forth? I’m almost always working on multiple projects all at once. But this is largely due to the fact that I work in a variety of mediums. While researching a longer novel, I can always divert myself by writing poetry, song lyrics, and picture books. That said, there comes a point where I have to put in my earbuds, turn on the “smooth brown noise,” tie my leg to the desk, and get the project done. No messing about. I’ll get a head of steam and everything else falls away. Thank you, Allan, there is much here to consider. I borrowed The Other Slavery: The Uncovered Story of Indian Enslavement in America by Andrés Reséndez. Please sure to leave a comment below. I will be entering names in for two Grand Prizes at the end of the month along with other give aways. One will be a copy of this book.  Welcome to 2021 National Poetry Month. It's my fifteenth year of participating (some years better than others). This year I'm taking a look at some previous poems that I enjoyed and will be revising. Some have been on the blog before and others not. I have five great interviews lined up: April 2 POETRY FRIDAY: ALLAN WOLF April 9 POETRY FRIDAY: LISA FIPPS April 16 POETRY FRIDAY: CHRIS BARON April 23 POETRY FRIDAY: JOANNE ROSSMASSLER FRITZ April 30 POETRY FRIDAY: LITA JUDGE I love getting books into the hands of readers so there will be prizes for stopping by and saying hi. |

AuthorAll photos and poems in these blog posts are copyrighted to Jone Rush MacCulloch 2006- Present. Please do not copy, reprint or reproduce without written permission from me. Categories

All

Archives

March 2024

2023 Progressive Poem

April 1 Mary Lee Hahn, Another Year of Reading April 2 Heidi Mordhorst, My Juicy Little Universe April 3 Tabatha, The Opposite of Indifference April 4 Buffy Silverman April 5 Rose Cappelli, Imagine the Possibilities April 6 Donna Smith, Mainely Write April 7 Margaret Simon, Reflections on the Teche April 8 Leigh Anne, A Day in the Life April 9 Linda Mitchell, A Word Edgewise April 10 Denise Krebs, Dare to Care April 11 Emma Roller, Penguins and Poems April 12 Dave Roller, Leap Of Dave April 13 Irene Latham Live You Poem April 14 Janice Scully, Salt City Verse April 15 Jone Rush MacCulloch April 16 Linda Baie, TeacherDance April 17 Carol Varsalona, Beyond Literacy Link April 18 Marcie Atkins April 19 Carol Labuzzetta at The Apples in My Orchard April 20 Cathy Hutter, Poeturescapes April 21 Sarah Grace Tuttle, Sarah Grace Tuttle’s Blog, April 22 Marilyn Garcia April 23 Catherine, Reading to the Core April 24 Janet Fagal, hosted by Tabatha, The Opposite of Indifference April 25 Ruth, There is no Such Thing as a God-Forsaken Town April 26 Patricia J. Franz, Reverie April 27 Theresa Gaughan, Theresa’s Teaching Tidbits April 28 Karin Fisher-Golton, Still in Awe Blog April 29 Karen Eastlund, Karen’s Got a Blog April 30 Michelle Kogan Illustration, Painting, and Writing |